… with Christian Palmer

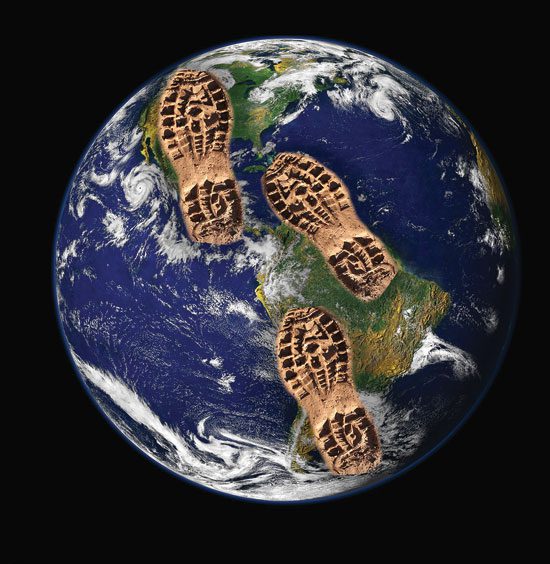

The need for a new geological epoch: The Anthropocene

In this monthly column, anthropology instructor and faculty chair of the sustainability curriculum committee Christian Palmer shares with us the latest developments WCC is taking toward becoming a more sustainable campus.

What is the Anthropocene? The Anthropocene is a proposed term for a new geological epoch that emphasizes the impact humans have had on the planetary scale. Right now, geologically speaking, we are in the Holocene, an epoch that began 11,700 years ago at the end of the last ice age.

Each geological epoch must be clearly marked in the geologic record, the layers of rock gradually formed through geological processes like volcanic eruptions and sedimentation. There is some debate between conservation scientists and geologists about whether or not human activities have provided this clearly marked transition.

The International Union of Geological Sciences, the group that determines the current naming system, is debating a proposal to officially accept the Anthropocene as a new geological epoch.

I would like to review several key arguments in favor of labeling the Anthropocene because I think it highlights the extent to which humans have impacted the planet and the importance of building an educational culture that begins to understand and address these environmental challenges. These include fossil fuels and climate change, nuclear weapons, new materials, physical changes to the earth’s surface and species extinctions.

First, the burning of fossil fuels like oil, gas and coal has released huge amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. This carbon dioxide traps heat from the sun in the atmosphere and changes global climate patterns, which can lead to ocean acidification, coral bleaching and a host of environmental challenges.

On a more basic scale, it changes the ratios of carbon isotopes (like carbon 13) that are used as the building blocks for all living things, a changing ratio that will be detectable in the fossil record indefinitely.

Second, since humans first exploded the atomic bomb in the 1940s, thousands of nuclear tests have been conducted, spreading new radioactive material across the surface of the earth. Because nuclear materials and the accompanying radiation can last for huge amounts of time, these materials will be visible in the fossil record well into the future. They can also pose health risks as they contaminate humans, plants, animals and waterways.

Third, humans are creating new materials that are being introduced into the geological record. This includes metals like elemental aluminum, which is not found naturally, and also construction materials like concrete, which is widely dispersed throughout human habitats. Humans have produced enough concrete to cover the entire globe.

In addition, plastics made from oils have become ubiquitous. Many have heard of the huge floating piles of plastic debris across the North Pacific, many of which make their appearance on Hawai‘i’s beaches. On the Big Island, geologist Patricia Concoran found plastiglomerates, or rocks from plastics, volcanic rocks, sand and shells. As these new materials become embedded in sedimentary rock layers, they become part of the geologic history of the earth.

Fourth, human activities like deforestation, urbanization, road building, agriculture and mining have altered roughly 50 percent of the earth’s surface, changing coastlines, the flow of rivers and other geological processes. These processes have led to species extinction because of habitat loss, the movement of plant and animals species across the globe and over exploitation of different species.

Although the earth’s surface has been constantly changing throughout the history of the planet and there have been multiple extinction events in the past, the current changes are different because they are anthropogenic, or caused by humans. What is even more telling is that humans are aware of the ongoing processes and are making decisions about how to address these issues.

The advantages of designating the current geological epoch as the Anthropocene is that it forces us, as a species, to consider the enormity of our impact and the ways that it crosses national and disciplinary boundaries. It should also help shape how and what we teach our young people.

In order to comprehend and respond to the challenges of living in the Anthropocene, we need to think about the problems across the traditional disciplines. Each of these issues has components that can be best understood through chemistry, ecology, politics, economics, art, business or music. No matter what career paths we choose, our education should prepare us to understand and survive in the geological epoch we inherit.